Description

FOCUS QUESTION 2:

How did the Wilson administration mobilize the home front? How did these mobilization efforts affect society?

After many months of fighting to stay neutral, President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany and the Central Powers on April 2, 1917. In spite of U-boat attacks that had taken the lives of many Americans and evidence that Germany was provoking Mexico to declare war on the United States, not all Americans agreed with the decision to go to war. In response to dissent, Congress passed the United States Sedition Act in May 1918. This Primary Source Exercise explores the opposing ideals of liberty and security that surrounded America’s entry into World War I. Compare them to the recent history of the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center in New York and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. After these attacks, Congress quickly passed the Patriot Act, which gave law enforcement entities wide powers of surveillance, data collection, and the ability to profile and detain suspected terrorists without cause or warrant. Many have asked in the decade since if Americans were too quick to give up so much liberty for security. As you examine the documents in this exercise, ask yourself, is it a sign of weakness that not everyone agrees about significant actions such as a declaration of war? Can dissent rise to a level where it will cause disruption and instability at home? If it can, can we tolerate any at all? Should we head off potential threats before there is any evidence of a certain threat? Just how hard should the government work to compel Americans to support a war?

DOCUMENTS

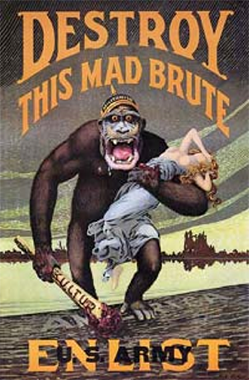

Document 1 is an army recruitment poster. “DESTROY THIS MAD BRUTE–Enlist U.S. Army” is the caption of this World War I propaganda poster for enlistment in the U.S. Army. This is a U.S. version of an earlier British poster with the same image.

Document 2 is the United States Sedition Act passed by Congress on May 16, 1918, as part of the Espionage Act. Both the Espionage Act and the Sedition Act were repealed in 1921, but major portions of the Espionage Act remain part of U.S. law (18 USC 793, 794) and form the legal basis for law concerning most classified information. However, the Espionage Act and the Sedition Act, as named, no longer exist.

INSTRUCTIONS

1. Read Chapter 22 of the textbook, with special attention to the introduction on page 895 and Mobilizing a Nation, pages 907-914.

2. Analyze Document 1 and read Document 2.

3. Answer the Focus Question.

DOCUMENT 1

Army Recruitment Poster, “Destroy the Mad Brute,” ca. 1917

A drooling, mustachioed ape wielding a club bearing the German word “kultur” and wearing a “pickelhaube” helmet with the word “militarism” is walking onto the shore of America while holding a half-naked woman in his grasp (possibly meant to depict Liberty).

Credit: Library of Congress

DOCUMENT 2

The United States Congress, Sedition Act (a portion of the amendment to Section 3 and Section 4 of the Espionage Act), 1918

Sec. 3.

Whoever, when the United States is at war, shall willfully make or convey false reports or false statements with intent to interfere with the operation or success of the military or naval forces of the United States, or to promote the success of its enemies, or shall willfully make or convey false reports or false statements, or say or do anything except by way of bona fide and not disloyal advice to an investor or investors, with intent to obstruct the sale by the United States of bonds or other securities of the United States or the making of loans by or to the United States, and whoever when the United States is at war, shall willfully cause or attempt to cause, or incite or attempt to incite, insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, or refusal of duty, in the military or naval forces of the United States, or shall willfully obstruct or attempt to obstruct the recruiting or enlistment services of the United States, and whoever, when the United States is at war, shall willfully utter, print, write or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States or the Constitution of the United States, or the military or naval forces of the United States, or the flag of the United States, or the uniform of the Army or Navy of the United States into contempt, scorn, contumely, or disrepute, or shall willfully utter, print, write, or publish any language intended to incite, provoke, or encourage resistance to the United States, or to promote the cause of its enemies, or shall willfully display the flag of any foreign enemy, or shall willfully by utterance, writing, printing, publication, or language spoken, urge, incite, or advocate any curtailment of production in this country of any thing or things, product or products, necessary or essential to the prosecution of the war in which the United States may be engaged, with intent by such curtailment to cripple or hinder the United States in the prosecution of war, and whoever shall willfully advocate, teach, defend, or suggest the doing of any of the acts or things in this section enumerated, and whoever shall by word or act support or favor the cause of any country with which the United States is at war or by word or act oppose the cause of the United States therein, shall be punished by a fine of not more than $10,000 or the imprisonment for not more than twenty years, or both: Provided, That any employee or official of the United States Government who commits any disloyal act or utters any unpatriotic or disloyal language, or who, in an abusive and violent manner criticizes the Army or Navy or the flag of the United States shall be at once dismissed from the service. . . .

Sec. 4.

When the United States is at war, the Postmaster General may, upon evidence satisfactory to him that any person or concern is using the mails in violation of any of the provisions of this Act, instruct the postmaster at any post office at which mail is received addressed to such person or concern to return to the postmaster at the office at which they were originally mailed all letters or other matter so addressed, with the words “Mail to this address undeliverable under Espionage Act” plainly written or stamped upon the outside thereof, and all such letters or other matter so returned to such postmasters shall be by them returned to the senders thereof under such regulations as the Postmaster General may prescribe.

Approved, May 16, 1918.

Also, there are some resources from American- A Narrative History V2